How Silicon Valley Bank Went Bust

The “Silicon Valley” in Silicon Valley Bank suggests some exotic technology exposure was behind the bank’s collapse—an encouraging thought, if your bank has nothing to do with Silicon Valley. But what broke Silicon Valley bank was something much more mundane: interest rate risk. To understand it, it helps to recall two slightly counterintuitive concepts: bank assets and liabilities, and the relationship between interest rates and bond values.

Bank Assets And Liabilities

Our deposits at a bank are our assets, but the bank’s liabilities, because at some point, we (or our heirs) are going to pull those deposits out. Similarly, if we borrow from a bank, that’s a liability for us, but an asset for the bank, since we ultimately have to pay interest and principal back on our loan. In the case of Silicon Valley Bank, it had a lot more deposits than it could lend out, so it put most of the rest of its deposits in bonds, or bond-like instruments like mortgage-backed securities.

Interest Rates And Bond Values

As interest rates go up, bond prices go down. That may seem counter intuitive, because, all else equal (same risk), who wouldn’t want a higher yield? The answer is that when interest rates go up, the coupon on already issued bonds stays the same, so to make their yields competitive to new buyers, the price has to go down (since coupon/price = yield, and all else equal, the smaller the denominator, the larger the yield).

What Happened To SVB When Yields Went Up

One way to increase yields is to buy bonds with longer-dated maturities, since those usually yield more than shorter-dated ones. That’s what Silicon Valley Bank did, essentially (though they also bought bond-like mortgage-backed securities). Fixed income securities with longer-dated maturities are also more sensitive to interest rate movements though. So when interest rates went up, the market value of Silicon Valley Bank’s fixed income securities went down. To shore up its balance sheet, the bank’s parent company, SVB Financial Group (SIVB), sought to raise more capital; that was interpreted as a sign of weakness by its Silicon Valley depositors, and the Silicon Valley bank run was on.

Could SVB Have Prevented This?

Sure. They could have hedged their interest rate risk. Why didn’t they? I don’t know, but it looks like the Head of Financial Risk Management & Model Risk at their UK subsidiary had other priorities, such as heading the LGBTQ+ employee resource group and helping to

spread awareness of lived queer experiences, partner with charitable organizations, and above all, create a sense of community for our LGBTQ+ employees and allies.

Protecting Yourself From Your Bank

In times like these, I’m glad I picked my bank from the list of strong ones in the back of Ravi Batri’s 1987 bestseller, “The Great Depression of 1990”.

True story: my bank has about a half-dozen branches, and has been around since the late 19th Century, having survived The Great Depression and the Global Financial Crisis without issue.

Hedging Your Bank’s Stock

For those of you with accounts at large, publicly-traded banks, in addition to keeping your account size below the FDIC insured limit, you might consider hedging the shares of your bank’s holding company. If your bank gets into trouble, its shares will plummet, and the value of your hedge will spike.

Thinking back to 2008, it was about six months between the collapse of Bear Stearns and the collapse of Lehman Brothers, so you might consider a hedge with an expiration 6 months or more out; if that’s very expensive, you might look at using shorter expirations, or moving your money to a different bank that’s cheaper to hedge.

Another thing you can do to reduce your cost of hedging, is hedge against a large decline. In this kind of market, even shares of strong companies might drop 10 or 20% in short order; maybe try scanning for hedges against declines of more than 40%. Here are two examples.

Hedging JPMorgan Chase & Co. (JPM). JPM shares were actually up on the day Friday, suggesting investors aren’t too worried about it at the moment. Its hedging cost, relatively speaking suggests that too. As of Friday’s close, these were the optimal puts to hedge 1,000 shares of JPM against a >40% decline by September. I’ve circled the annualized cost as a percentage of position value, so we can compare apples-to-apples here.

Screen captures via the Portfolio Armor iPhone app.

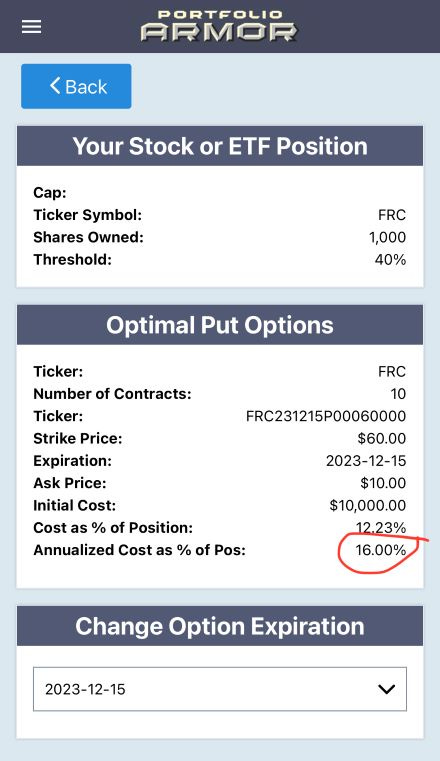

Hedging First Republic Bank (FRC). This one was down nearly 15% on Friday, suggesting investors are somewhat concerned this San Francisco-based regional bank have similar issues as Silicon Valley Bank did. Again, this was mirrored in its hedging cost. These were the optimal puts, as of Friday’s close, to hedge it against a >40% decline by December.

As you can see, the annualized cost as a percentage of position value was more than 10x as high for FRC as it was for JPM.